"Canonicity" is the perfect metaphor for becoming an adult. Small children learn (to a greater or lesser extent) that the world is made out of strict, absolute rules. They soon come to expect those rules to be both internally and mutually consistent, and the more so they appear to be, the more the child becomes attached to, and identifies with, those rules. As we grow up, and our critical sense develops, many of us start to see that more than one rule is possible, and that some rules don't work in all situations, and some rules from the past are incompatible with rules in the present. And some present rules are incompatible with our experience and observation.

Eventually we realize that what we thought were rules were barely even guidelines. They were intended as simplification - either by us or for us - to give children a means of interacting with a complex, confused and conflicted adult world.

An adult is someone who judges each situation on its present context. Who seeks information, guidance and suggestions from other adults, but who ultimately decides that what is right at any given place and time is what feels right within the present context. It is a sign of immaturity to seek to fit a present context into its place in a set of established rules.

Fiction, in the obvious cases of fairytales, fantasy and (much) science fiction, but in almost every genre, is about rules. Vampires can't go out during the day, police officers must follow procedure, cowboys are bound to being the good guy or the bad guy, and can't go against this even if it is in their nature to do so*. Pterry calls these rules "narrative causality" and with good reason. We teach the rules of our culture to eachother by telling stories.

But... the oldest stories we know are about heroes. And heroes break rules. Orpheus goes into the underworld to bring Eurydice back from the dead (in Zena people go back and forth so much to the underworld that Cerberus is put out to stud and Hades fits a revolving door (at least, I assume so)); Perseus kills anything and everything it's forbidden to kill - Heracles succeeds at every task which has been set him, even though he has been set these tasks by a god who intends him to fail.

Stories about heroism are indeed stories about becoming an adult; taking responsibility, having the courage of your convictions (a favourite expression of my prep-school Headmaster Alan Butterworth) - what I love about this idea is that it suggests that even if your convictions may be wrong, you should still do what you feel is the right thing.

Argument over what is canon and what is not are particularly impossible in Dr Who. Much fun is being had by the series' present creators at the moment to stimulate a controversy about how many regenerations a timelord can have. The series is 50 years old. Hundreds of people have contributed to the Dr Who universe over those years, and they can't all agree though some have tried — heroically — to create stories that reconcile apparently conflicting rules.

Personally, I think there is more meaning to be found in looking at the way that the rules of a fantasy universe, or a folk tale, evolve with each retelling. As an author, there is a huge amount to be learned from reading The Hobbit first, then LOTR, then the Silmarillion. The major cultural flaw of the new Hobbit films is exactly what its makers all to obviously think is its strength: that the audience already knows what happens later, what the real meaning of the Ring and the Necromancer are.

But of course, when the Hobbit was written, the ring was just a magic ring that made you invisible, and the Necromancer just a nebulous and distant threat - something to be avoided, and no more.

Bilbo's ring is retconned into The One Ring; Gollum is retconned into Sméagol; the Necromancer is retconned into Sauron.

Inspiration is essential to the storyteller's art; and just as you can be inspired to write your own story by someone else's, so you can be inspired to write a new story by one of your own stories.

Damon Courtney is very close to releasing the third in his Dragon Bond series, and the third book is a culmination of a process of ongoing development - an expanding fantasy world; an expanding canon. A hero of the third book was little more than a mook in the first and a pawn in the second. But Damon was inspired by what the character was becoming.

To a considerable extent, what we add to the world of the series in later books can be seen as what we did not know. When we read The Hobbit as children, we thought Bilbo's ring was just a magical trinket, and very convenient considering his, ahem, profession. But when we read LOTR, we can choose to accept that in reality there were all sorts of things we did not know; could not know. LOTR shows us that no story exists in a vacuum; no story is an island — what contributes to a story may have causes and consequences far outside that story.

Which is what we learn about real life, when we become adults; the real world does not have convenient beginnings and endings. The real world is all middles.

____

* the most recent example of this is Vimes, who believes himself to be a bad guy, but is incapable of resisting the urge to do the right thing.

2013-12-16

2013-11-13

Weird Words #7: Instinctual or Instinctive?

Instinct is a tricky beast. So often we think we are or we think we aren't acting on it, and so often we might — or might not — be wrong.

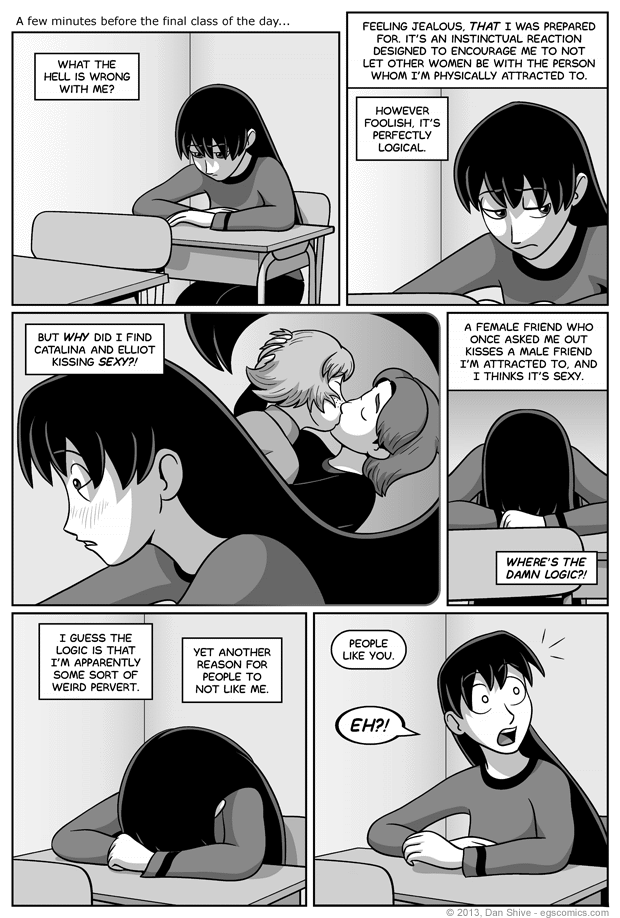

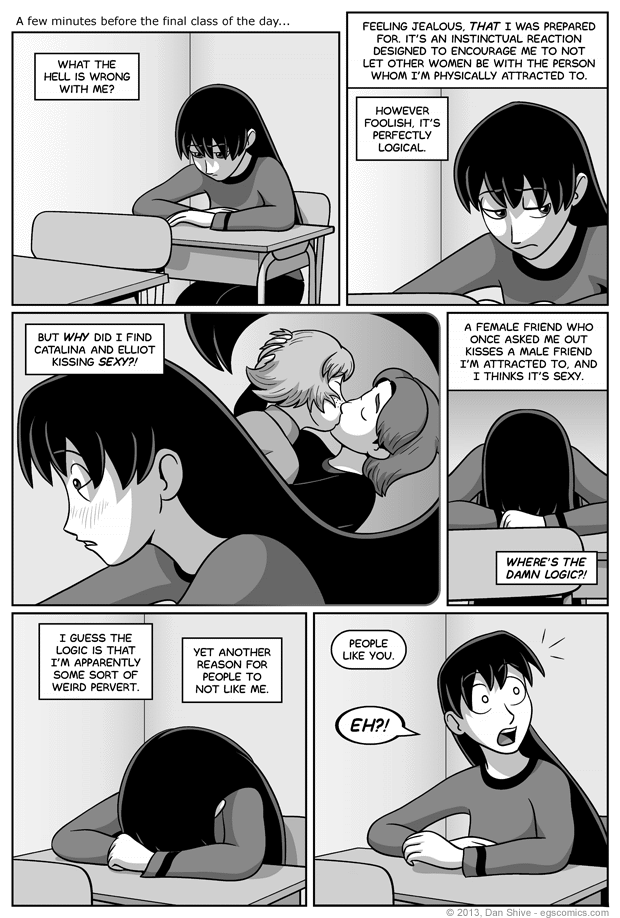

My thanks go to the Dan Shive for prompting this post... I hope he reads it.

Writers, and everyone else for that matter, write a lot of bunk about instinct. Much of it can probably be avoided except for where it is strictly thematic, but all that is beside the point. Today's issue is the word instinctual.

Now this word is not the modern invention it appears to be to people who grew up with instinctive and only encountered instinctual from time to time. Although it appears to date from the mid nineteenth century*, whereas instinctive is from the early seventeenth, there should be, and often is, a distinction in the meaning between these two words.

Both words are about instinct — whatever you think that might be. But they have different suffixes for a reason.

The -ive suffix typically means: arising from, pertaining to, tending to.

The -al (often -ual) suffix typically means: of, like, relating to.

In modern English there is often some overlap between these but consider the following imaginary University Facluties:

Department of Instinctual Studies — Department of Instinctive Studies

I hope some readers will immediately feel the difference in meaning, I'm sure that some will see it straight away. For those that don't:

The Department of Instinctual Studies studies and teaches about instinct. The Department of Instinctive Studies studies or teaches through or using instinct. We don't know what it teaches.

To put it another way, instinctual studies is the "of" meaning of the -al suffix: "the study of instinct". Instinctive studies is the "arising from" or "tending to" meaning of the -ive suffix, meaning study using instinct.

What I find especially curious is that there are very few words ending in -ual compared with those ending in -ive. So few, indeed, that a list of those that have both can be very short:

I think this shows that there is a valid, definite and valuable distinction between the meanings of instinctive and instinctual and writers should stop using the latter as a "smarter sounding alternative" to instinctive. In fiction, usage of instinctual ought to be extremely rare compared with instinctive.

However!

I can't work out whether there should or could be a clear denotative difference between instinctually and instinctively. The former seems only to be used by people who use instinctual when they mean instinctive and I suspect that this is why four out of five of the dictionaries I regularly go to have no listing for instinctually at all.

___

* Some sources put the word later, in the early twentieth. It appears very often in translations of German psychology textbooks and hardly anywhere else until the 1960s, and it is only from the 1980s that it really starts to become common.

My thanks go to the Dan Shive for prompting this post... I hope he reads it.

Writers, and everyone else for that matter, write a lot of bunk about instinct. Much of it can probably be avoided except for where it is strictly thematic, but all that is beside the point. Today's issue is the word instinctual.

Now this word is not the modern invention it appears to be to people who grew up with instinctive and only encountered instinctual from time to time. Although it appears to date from the mid nineteenth century*, whereas instinctive is from the early seventeenth, there should be, and often is, a distinction in the meaning between these two words.

Both words are about instinct — whatever you think that might be. But they have different suffixes for a reason.

The -ive suffix typically means: arising from, pertaining to, tending to.

The -al (often -ual) suffix typically means: of, like, relating to.

In modern English there is often some overlap between these but consider the following imaginary University Facluties:

Department of Instinctual Studies — Department of Instinctive Studies

I hope some readers will immediately feel the difference in meaning, I'm sure that some will see it straight away. For those that don't:

The Department of Instinctual Studies studies and teaches about instinct. The Department of Instinctive Studies studies or teaches through or using instinct. We don't know what it teaches.

To put it another way, instinctual studies is the "of" meaning of the -al suffix: "the study of instinct". Instinctive studies is the "arising from" or "tending to" meaning of the -ive suffix, meaning study using instinct.

What I find especially curious is that there are very few words ending in -ual compared with those ending in -ive. So few, indeed, that a list of those that have both can be very short:

| actual | active | (the meanings are very distinct) |

| auditual | auditive | (the latter is vastly more common but both are just synonyms for auditory) |

| effectual | effective | (the former means "having an effect" and is more often used negated. The latter means performing its expected function) |

| perceptual | perceptive | the difference is very similar to instinctual/instinctive: perceptual is "all about perception" while perceptive is "possessing qualities or capacities of perception" |

I think this shows that there is a valid, definite and valuable distinction between the meanings of instinctive and instinctual and writers should stop using the latter as a "smarter sounding alternative" to instinctive. In fiction, usage of instinctual ought to be extremely rare compared with instinctive.

However!

I can't work out whether there should or could be a clear denotative difference between instinctually and instinctively. The former seems only to be used by people who use instinctual when they mean instinctive and I suspect that this is why four out of five of the dictionaries I regularly go to have no listing for instinctually at all.

___

* Some sources put the word later, in the early twentieth. It appears very often in translations of German psychology textbooks and hardly anywhere else until the 1960s, and it is only from the 1980s that it really starts to become common.

2013-11-04

Genre Tyranny - and a couple of apologies.

First an apology. I've been nagging Dawn McCullough-White to write a sequel to The Emblazoned Red. This is partly because I really like this book and partly because I really like Dawn's work in general. There's something very particular about the experience of reading it; an atmosphere, a sense of presence, that seems to be unique to her style and presentation, and imagination.

My apology is that while I have already mentioned the book on my blog, until today, the cover was not on the right hand column of this page. I don't know what difference, if any, that would make to readers discovering this book that certainly deserves to be discovered, but it's something I ought to have done, and have not.

I'm also apologizing to Ray Kingfisher, whose excellent, slick, funny Easy Money has also not shown on this page. Easy Money is dedicated to the late Tom Sharpe who died in June of this year. If you read it, you will see why.

The Emblazoned Red is a book that manages to combined the defining characteristics of several genres into a coherent, convincing, artfully imagined world. But it really doesn't conform to any of those genres. It reads like a regency romance, but the main character is an armoured knight who fights the undead and falls in love with a pirate.

If you sat down and said: "I'm going to combine vampires, zombies, pirates, paladins and highwaymen into a bodice ripper" you'd surely have a recipe for disaster, but a good book doesn't come from a recipe.

It comes from a strong story idea, that is worked into a strong story; that has characters that you care about, that compel your interest and attention. That is what Dawn delivers. That it takes place in an imaginary world where the difference between living and dead is ... less clearly defined than in our own ... is just part of her creative vision. I find her world-building almost effortlessly transporting even when it is a little sparse. So the lack of a true, defining genre shouldn't represent a problem.

But the organ by which we distribute our works depends on classification. How else can one writer claim he is #1 in Books > Science Fiction & Fantasy > Science Fiction > Post-Apocalyptic and another be #1 in Books > Science Fiction & Fantasy > Science Fiction > Steampunk and so on. All this enables readers to find what they want and the maximum number of writers get the maximum of exposure.

Provided they are writing genre fiction. Amazon has a category Books > Literature & Fiction > Literary. Honestly it's a bucket. The last place you want to be if you want to get noticed, and look at any book in the top ten in that category and you'll see that it has a high ranking in two or three other categories.

It's all about the categories.

Which is a pity, I think. I wonder how many readers do not actively seek the next Kindle Store > Kindle eBooks > Literature & Fiction > Women's Fiction > Sagas or Kindle Store > Kindle eBooks > Literature & Fiction > Contemporary Fiction > American... and just want to read a good book, regardless of how it is categorized.

If I searched by category for the the type of book I thought I might like, I'm pretty sure I'd never have encountered any of Dawn McCullough-White's work.

My apology is that while I have already mentioned the book on my blog, until today, the cover was not on the right hand column of this page. I don't know what difference, if any, that would make to readers discovering this book that certainly deserves to be discovered, but it's something I ought to have done, and have not.

I'm also apologizing to Ray Kingfisher, whose excellent, slick, funny Easy Money has also not shown on this page. Easy Money is dedicated to the late Tom Sharpe who died in June of this year. If you read it, you will see why.

The Emblazoned Red is a book that manages to combined the defining characteristics of several genres into a coherent, convincing, artfully imagined world. But it really doesn't conform to any of those genres. It reads like a regency romance, but the main character is an armoured knight who fights the undead and falls in love with a pirate.

If you sat down and said: "I'm going to combine vampires, zombies, pirates, paladins and highwaymen into a bodice ripper" you'd surely have a recipe for disaster, but a good book doesn't come from a recipe.

It comes from a strong story idea, that is worked into a strong story; that has characters that you care about, that compel your interest and attention. That is what Dawn delivers. That it takes place in an imaginary world where the difference between living and dead is ... less clearly defined than in our own ... is just part of her creative vision. I find her world-building almost effortlessly transporting even when it is a little sparse. So the lack of a true, defining genre shouldn't represent a problem.

But the organ by which we distribute our works depends on classification. How else can one writer claim he is #1 in Books > Science Fiction & Fantasy > Science Fiction > Post-Apocalyptic and another be #1 in Books > Science Fiction & Fantasy > Science Fiction > Steampunk and so on. All this enables readers to find what they want and the maximum number of writers get the maximum of exposure.

Provided they are writing genre fiction. Amazon has a category Books > Literature & Fiction > Literary. Honestly it's a bucket. The last place you want to be if you want to get noticed, and look at any book in the top ten in that category and you'll see that it has a high ranking in two or three other categories.

It's all about the categories.

Which is a pity, I think. I wonder how many readers do not actively seek the next Kindle Store > Kindle eBooks > Literature & Fiction > Women's Fiction > Sagas or Kindle Store > Kindle eBooks > Literature & Fiction > Contemporary Fiction > American... and just want to read a good book, regardless of how it is categorized.

If I searched by category for the the type of book I thought I might like, I'm pretty sure I'd never have encountered any of Dawn McCullough-White's work.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)