"Are you sure you know the way?" she asked me.

I stood in thought. This was one of the big mysteries of the adult brain — or so I thought — beyond yes and no. Shortly before, she had asked me if I knew the way to room 88. I did know the way, and at (I guess) age 12 or so, that was all there was, so I said so:

"Sure? You asked me if I knew the way, and I said yes. That's all there is. I know, or I don't know. I don't know anything about 'sure'."

She gave me one of those long, faraway stares that adults do when you give them an answer that bears no relation to the expected "yes" or "no". Scratch that – one of those looks that everyone gives me all the time. As far as I was concerned, she started it, by going beyond "yes" or "no" in the first place.

"So you're not so sure, huh?" I used to think this was trying to convince the child he must be in the wrong because he's a child. I have sometimes caught myself doing that to my own children, so other people must do it too, right? Sometimes though, I think it's just taking refuge in a familiar place: the child is getting pedantic, so he must be trying to distract from his lack of certainty.

***

"Are you sure you won't have another biscuit?"

I know that one mustn't get snippy with well-meaning elderly aunts. Although I still find this one a trial, I at least know what I'm supposed to do here. Aged 8 or 9 this time, the utterly baffling back-and-forth over who should do what for whom was a source of annoyance when I had to observe it in others and of acute personal discomfort when I got caught up in it myself.

***

It wasn't until I had children of my own that I learn just how relative yes and no really are. To children, the parent's "no" means something like "not until next time you ask me" or in worse cases "go ask your other parent". Similarly, the child's "yes" when asked anything along the lines of "have you done what you know you were supposed to do" really means "what kind of trouble will I get into if you find out the real answer is no?"

We paint ourselves a comforting fiction that a simple "yes" or "no" is equivalent to "done" and "not done" (to borrow from T H White) - that it can only mean one thing. And yet we know that when the kids in the back seat say "are we nearly there yet" that for a long time the answer will be "no", but at some point it will magically become "yes", even though the question and the conditions under which it is asked are unchanged. It is a short leap from this to asking for an icecream every thirty seconds.

Those negotiations over biscuits, those demands of sureness, are rather clumsy ways of getting past the artificial barrier of "yes" and "no", and through to real desires and the reliability of knowledge. Had I know that, I would have known that the proper response to "are you sure you know the way" was:

"I know the route seems a little convoluted, but I have to come here at least once every day."

I would also have known that the best reply over the biscuits was to get out of trouble by not answering the question but making a general statement:

"I won't have another biscuit."

or, more politely:

"I've had enough to eat, thanks."

***

Edward de Bono wrote a short book that I can strongly recommend called "beyond yes and no". He is dealing with the perpendicular issue of how yes and no often result in an attempt at a preconfigured solution to every problem, rather than what he recommends, which is to apply a general approach, which he calls "policy" or simply "P".

Insisting to ourselves on the sanctity of yes and no is to try to penetrate other people's thoughts by separating the cream from the coffee. What we know about what goes on inside others' heads is not polar. This is mostly because what we know, and what others know, is not clear, or certain. I am convinced that we cannot be "sure". However this doesn't invalidate yes, no, nor the question "are you sure". These are tools used in a process by which we discover what other people think they know, and then decide how reliable that knowledge is.

From this point of view, a simple iterative process enables you to decide whether to follow the (rather pompous) 12 year old schoolboy through the labyrinthine corridors of the Victorian school building.

You observe his demeanour when you ask "do you know the way?". Realizing that he is likely to have learned to appear confident in every response, you decide to dig a little further than his forthright "yes". You'd be smart to do better than "are you sure?" though. You could attempt "how do you know?" or even "why are you sure?". Anything to provoke a further response that is on topic. You'll respond to the tone, the body language, as much as to the words themselves. (After all, I could be lying about going there every day.) And then, according to your confidence or otherwise you'll either declaim "lay-on, MacDuff" or wander off in search of some other insufferable, spotty, floppy-haired public schoolboy.

***

"Answer the question, yes or no!"

This is always a ruse. Sometimes the answer isn't "yes" and it isn't "no". If so, stick to your guns. Insist. Give the real answer.

2011-10-31

2011-10-18

Off Topic #2: Design

Following on from yesterday's not really off-topic post, here is another one, even less off topic, though perhaps seeming more so…

Design is dead.

Time there was, in production fabrication and construction, the designer was the single most important contributor to development. Today, few people even understand what, back in their heyday in the nineteenth century, designers actually did, and when I point out exemplary pieces of period design, many folks will comment "Oh yes, there's lots of design on that".

Time there was, in production fabrication and construction, the designer was the single most important contributor to development. Today, few people even understand what, back in their heyday in the nineteenth century, designers actually did, and when I point out exemplary pieces of period design, many folks will comment "Oh yes, there's lots of design on that".

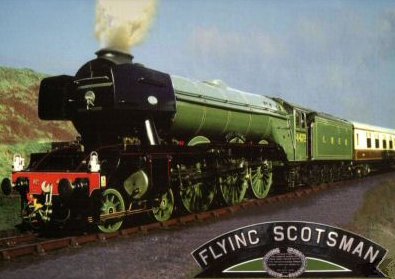

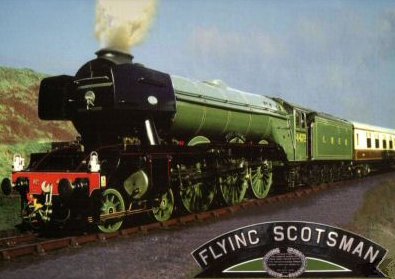

Somehow, design has come to mean "adding the pretty, nonfunctional details". Movements like Bauhaus are partly to blame. Bauhaus elevated design to an art form, but what made Bauhaus so aesthetically and ergonomically pleasing was its concentration on the principles that drove C18 and C19 engineering - the key being design. In the C19, design was the careful balance of functional requirements at all stages of the life-cycle of a product. The designer would, when deciding what his product would look like, take account of materials and their cost and availability, the cost, time and skill required for fabrication, the required durability, the costs of future maintenance, the necessity of future-proofing or backwards-compatibility (a couple of ideas that, under a variety of names, have been know since at least ancient Rome). The skill of some designers as the end of the nineteenth century approached was so great that they could afford to build-in beauty as a concomitant feature. In many areas of engineering, this idea continued through to the 1950s, and such visually divergent designs as Scotsman and Mallard…

… which solve similar practical problems but with strikingly different visual consequences. Both are beautiful, because their beauty goes so much further than external prettiness.

The high profile and high public approval of these kinds of design, combined with Bauhaus (and its imitators) elevation of aesthetics – or perhaps the elevation of Bauhaus by the popular press – resulted in a separation between the visual appearance of a product and its engineered function. Creative people with little or no knowledge of manufacture were brought in to "design" products to make them pleasing to the eye, popular, fashionable. These "designs" were then passed on to fabricators whose job was to find a way to manufacture something that looked like the designs.

This is how things are today. The real skill of fabrication is working out how to make something. Wherever this is understood, there are no designers at all; engineers invent, plan and build. The results seldom meet needs even when they meet requirements. (You know who you are.) Wherever there are designers, the engineers are woefully undervalued. Beauty has been divorced from function – indeed one often hears the two being described as in conflict: "a triumph of form over function" … "plain practicality".

To the engineers of the nineteenth century, as much as to the public who used their products, any design that solved a problem efficiently was inherently beautiful, and the satisfaction that they derived from the inherent beauty of a good solution, gave them the confidence to draw the bold flowing curves of the Mallard, and put Greek and Roman column capitals on gasometers.

In creative writing, design is seen by many as a sort of sell-out, betrayal or even circumvention of the artistic process. I have encountered this attitude as much in commercial writing as in novel writing. Setting aside marketing copy, novel writing is not, as many authors think, storytelling.

It has been accurately stated that the written word is the worst thing ever to happen to storytelling. Storytelling truly is an organic, creative, social process. When you tell a story to an audience, the audience responds to you and you to them. The story changes as it enters the imaginative space between you and your audience, and is different at each telling. Those of your audience whose imagination is captivated, will pass on your story to others, and it will change for them just as it changed for you.

When you write it down, it is the same every time you read it.

This gives you a problem to solve. How to tell the story that you want to tell, how to reach your audience when you don't have their reactions and you don't even know who they are? When you have a problem to solve, there is value in having a design. How far you take it is up to you – and is probably a function of your knowledge and experience. I suspect that many authors write as if they were telling a story with themselves as audience – which would explain the common observation by the author that the story took unexpected twists and turns, and that characters appeared, developed and evolved in unanticipated ways.

This stage is the discovery of the story. In storytelling, you discover the story either by being told it, or by telling it to yourself. Once you know your story, the practical problem to which you must return is "how to tell it using the written word". Most authors apply an iterative design process. Drafting and redrafting. Many authors involve third parties like beta-readers, proofreaders and editors (each of these has a different purpose and they should be selected to match your design process. Not every author can benefit from a literary editor). I guess the big advantage of novel writing is the possibility of design-after-the-fact. (I nearly said that in Latin, but I suspect that italics and hyphens is going to reach a larger audience.) Once you know the story, and have tried it out a few times, you can have several gos at writing it. My client, new writer Damon Courtney, has just sent me a redraft where he has made very substantial changes to the book, in structure, character dynamics, setting - even the outcome of major events (a party that had been planned then cancelled in the previous draft actually takes place in the new draft). The new draft is nonetheless the same story. But Damon has redesigned the way it is told to better match the medium: the written word.

The differences between "The Resurrection of Deacon Shader" and the rewriting "Shader: Cadman's Gambit" and "Shader: Best Laid Plans" are more than substantial. It's more a case of a few passages and characters from Resurrection being re-used in a new book. New book, same story.

If you are already a great author, chances are you probably ought to carry on doing whatever it is you do. If you want to become a great author, designing a book is complex and difficult. But worth it.

Design is dead.

Time there was, in production fabrication and construction, the designer was the single most important contributor to development. Today, few people even understand what, back in their heyday in the nineteenth century, designers actually did, and when I point out exemplary pieces of period design, many folks will comment "Oh yes, there's lots of design on that".

Time there was, in production fabrication and construction, the designer was the single most important contributor to development. Today, few people even understand what, back in their heyday in the nineteenth century, designers actually did, and when I point out exemplary pieces of period design, many folks will comment "Oh yes, there's lots of design on that".Somehow, design has come to mean "adding the pretty, nonfunctional details". Movements like Bauhaus are partly to blame. Bauhaus elevated design to an art form, but what made Bauhaus so aesthetically and ergonomically pleasing was its concentration on the principles that drove C18 and C19 engineering - the key being design. In the C19, design was the careful balance of functional requirements at all stages of the life-cycle of a product. The designer would, when deciding what his product would look like, take account of materials and their cost and availability, the cost, time and skill required for fabrication, the required durability, the costs of future maintenance, the necessity of future-proofing or backwards-compatibility (a couple of ideas that, under a variety of names, have been know since at least ancient Rome). The skill of some designers as the end of the nineteenth century approached was so great that they could afford to build-in beauty as a concomitant feature. In many areas of engineering, this idea continued through to the 1950s, and such visually divergent designs as Scotsman and Mallard…

… which solve similar practical problems but with strikingly different visual consequences. Both are beautiful, because their beauty goes so much further than external prettiness.

The high profile and high public approval of these kinds of design, combined with Bauhaus (and its imitators) elevation of aesthetics – or perhaps the elevation of Bauhaus by the popular press – resulted in a separation between the visual appearance of a product and its engineered function. Creative people with little or no knowledge of manufacture were brought in to "design" products to make them pleasing to the eye, popular, fashionable. These "designs" were then passed on to fabricators whose job was to find a way to manufacture something that looked like the designs.

This is how things are today. The real skill of fabrication is working out how to make something. Wherever this is understood, there are no designers at all; engineers invent, plan and build. The results seldom meet needs even when they meet requirements. (You know who you are.) Wherever there are designers, the engineers are woefully undervalued. Beauty has been divorced from function – indeed one often hears the two being described as in conflict: "a triumph of form over function" … "plain practicality".

To the engineers of the nineteenth century, as much as to the public who used their products, any design that solved a problem efficiently was inherently beautiful, and the satisfaction that they derived from the inherent beauty of a good solution, gave them the confidence to draw the bold flowing curves of the Mallard, and put Greek and Roman column capitals on gasometers.

In creative writing, design is seen by many as a sort of sell-out, betrayal or even circumvention of the artistic process. I have encountered this attitude as much in commercial writing as in novel writing. Setting aside marketing copy, novel writing is not, as many authors think, storytelling.

It has been accurately stated that the written word is the worst thing ever to happen to storytelling. Storytelling truly is an organic, creative, social process. When you tell a story to an audience, the audience responds to you and you to them. The story changes as it enters the imaginative space between you and your audience, and is different at each telling. Those of your audience whose imagination is captivated, will pass on your story to others, and it will change for them just as it changed for you.

When you write it down, it is the same every time you read it.

This gives you a problem to solve. How to tell the story that you want to tell, how to reach your audience when you don't have their reactions and you don't even know who they are? When you have a problem to solve, there is value in having a design. How far you take it is up to you – and is probably a function of your knowledge and experience. I suspect that many authors write as if they were telling a story with themselves as audience – which would explain the common observation by the author that the story took unexpected twists and turns, and that characters appeared, developed and evolved in unanticipated ways.

This stage is the discovery of the story. In storytelling, you discover the story either by being told it, or by telling it to yourself. Once you know your story, the practical problem to which you must return is "how to tell it using the written word". Most authors apply an iterative design process. Drafting and redrafting. Many authors involve third parties like beta-readers, proofreaders and editors (each of these has a different purpose and they should be selected to match your design process. Not every author can benefit from a literary editor). I guess the big advantage of novel writing is the possibility of design-after-the-fact. (I nearly said that in Latin, but I suspect that italics and hyphens is going to reach a larger audience.) Once you know the story, and have tried it out a few times, you can have several gos at writing it. My client, new writer Damon Courtney, has just sent me a redraft where he has made very substantial changes to the book, in structure, character dynamics, setting - even the outcome of major events (a party that had been planned then cancelled in the previous draft actually takes place in the new draft). The new draft is nonetheless the same story. But Damon has redesigned the way it is told to better match the medium: the written word.

The differences between "The Resurrection of Deacon Shader" and the rewriting "Shader: Cadman's Gambit" and "Shader: Best Laid Plans" are more than substantial. It's more a case of a few passages and characters from Resurrection being re-used in a new book. New book, same story.

If you are already a great author, chances are you probably ought to carry on doing whatever it is you do. If you want to become a great author, designing a book is complex and difficult. But worth it.

2011-10-17

Off Topic #1

If you follow me on Twitter you will have realized that the Winter Veg season has started in earnest. Last week's basket from the AMAP included black radishes which are delicious raw, baked, deep fried, pan fried, in soup, stuffing or made into condiment. I went for soup, as follows:

1 large black radish

2 large potatoes

2 small onions or 3-4 shallots

2 saucisses à cuire

salt, paprika, cayenne pepper, cumin seed

Serves four hungry people or two Russian peasants. Enough for about 6 middle-class English dinner guests.

Chop the shallots into small slices and put them in a hot frying pan with about 2 teaspoonfuls of lard (I prefer mixed lard for this but you can use fatback or caul). My lard is unbleached, untreated and comes from a local farm that has its own butchery. In general I advise getting your lard direct from the butcher or preparing it yourself.

Peel the radish and potatoes, and chop the potatoes into chunks and the radish into thinnish slices. As the shallots start to brown, add the potatoes and radishes, about a teaspoonful of paprika, a pinch of cayenne and a dozen or so cumin seeds. Keep the pan good and hot, and toss frequently.

While it is cooking, heat up a litre or two of water with about half a teaspoon of salt, slice up the sausage and drop it in the water. Let it come to the boil. (It helps if you have already had the sausage before, so you know how salty it is. This can vary quite a lot. With the saltier ones, there is no need to salt the water.

Once the potatoes and radishes start to brown, tip the entire contents of the frying pan in the boiling water. De-glaze the frying pan with about half a glass of red wine. (One the pan is empty, get it good and hot, and tip half a glass of red wine into it. It will boil instantly, and spit a little at first. Swirl it around so it cleans the pan.) Tip the remaining contents of the frying pan into the boiling water. You may need to scrape a little with a wooden spatula. I don't usually drink the last 3cm of any bottle of red. Instead I pour it into a bottle that I keep for the purpose, which is now a horrifying mixture of old wine. This is the best stuff for deglazing, or as a base for an instant marinade, or to add body to any braised dish.

Boil the lot for about 20 minutes.

Separate out all but 2 or three slices of sausage, and re-fry them in the same pan. While you are doing this, put the rest in the blender and blend it until smooth and creamy (your guests may even think there is cream in the soup. This is part of the magic of lard, even in tiny quantities). If you need to add water to make it blend well, then do. It will probably be too thick at this stage anyway. Once the sausage starts to brown, put it back in with the soup. De-glaze again, but this time use less wine. About a quarter glass topped up to half way with water - or you could use Beaujolais. All it's good for IMO.

With a steady heat on, add a little pre-boiled water from the kettle until you get the consistency you want. I advice tasting it to judge the consistency, rather than just going on the stirring resistance.

Here's my top soup serving tip: if you're worried you haven't made enough, serve it too hot to eat with a spoon but with lots of crusty bread. Your diners will fill up with bread dipped in soup. In any case the radish will still be quite lively if you haven't cooked it too long.

Like any proper winter soup, this is very filling. Also like any proper winter soup you can make it with any damn vegetable. I did another this week with parsnip and salsify. The latter takes a little more preparation. I daresay I'll rave about salsify some time soon.

1 large black radish

2 large potatoes

2 small onions or 3-4 shallots

2 saucisses à cuire

salt, paprika, cayenne pepper, cumin seed

Serves four hungry people or two Russian peasants. Enough for about 6 middle-class English dinner guests.

Chop the shallots into small slices and put them in a hot frying pan with about 2 teaspoonfuls of lard (I prefer mixed lard for this but you can use fatback or caul). My lard is unbleached, untreated and comes from a local farm that has its own butchery. In general I advise getting your lard direct from the butcher or preparing it yourself.

Peel the radish and potatoes, and chop the potatoes into chunks and the radish into thinnish slices. As the shallots start to brown, add the potatoes and radishes, about a teaspoonful of paprika, a pinch of cayenne and a dozen or so cumin seeds. Keep the pan good and hot, and toss frequently.

While it is cooking, heat up a litre or two of water with about half a teaspoon of salt, slice up the sausage and drop it in the water. Let it come to the boil. (It helps if you have already had the sausage before, so you know how salty it is. This can vary quite a lot. With the saltier ones, there is no need to salt the water.

Once the potatoes and radishes start to brown, tip the entire contents of the frying pan in the boiling water. De-glaze the frying pan with about half a glass of red wine. (One the pan is empty, get it good and hot, and tip half a glass of red wine into it. It will boil instantly, and spit a little at first. Swirl it around so it cleans the pan.) Tip the remaining contents of the frying pan into the boiling water. You may need to scrape a little with a wooden spatula. I don't usually drink the last 3cm of any bottle of red. Instead I pour it into a bottle that I keep for the purpose, which is now a horrifying mixture of old wine. This is the best stuff for deglazing, or as a base for an instant marinade, or to add body to any braised dish.

Boil the lot for about 20 minutes.

Separate out all but 2 or three slices of sausage, and re-fry them in the same pan. While you are doing this, put the rest in the blender and blend it until smooth and creamy (your guests may even think there is cream in the soup. This is part of the magic of lard, even in tiny quantities). If you need to add water to make it blend well, then do. It will probably be too thick at this stage anyway. Once the sausage starts to brown, put it back in with the soup. De-glaze again, but this time use less wine. About a quarter glass topped up to half way with water - or you could use Beaujolais. All it's good for IMO.

With a steady heat on, add a little pre-boiled water from the kettle until you get the consistency you want. I advice tasting it to judge the consistency, rather than just going on the stirring resistance.

Here's my top soup serving tip: if you're worried you haven't made enough, serve it too hot to eat with a spoon but with lots of crusty bread. Your diners will fill up with bread dipped in soup. In any case the radish will still be quite lively if you haven't cooked it too long.

Like any proper winter soup, this is very filling. Also like any proper winter soup you can make it with any damn vegetable. I did another this week with parsnip and salsify. The latter takes a little more preparation. I daresay I'll rave about salsify some time soon.

2011-10-10

Translation Time

It's reaching a point where significant numbers independent, e-Published authors are making big enough sales to think about getting translated.

I have worked as a freelance translator, and know a number of them. Freelance translators are the best way to go because they cut out the intermediaries and you get better rates.

All this is somewhat beside the point though, and the point is this:

If you already have a book written in English that is selling in the English-speaking world, you can do a simple bit of maths to see if getting it translated will be profitable. Supposing you have a 75k word novel that has sold a total of 5000 downloads for $1.50 (your profit - sales commission already deducted ). If your main market is US English, then include Canada, the UK and Australia to creep up to a population of about 500M. This isn't the size of your market, but it's the only figure you need to work out if translation will be profitable (or when it will be).

France has a population of about 60M. They all speak French well enough to read your book in French. "Standard" French is also spoken as a first or second language in numerous other countries around the world, though experience tells me that estimates of how many speak it as well or nearly as well, or the same way or nearly the same way as in mainland France are deeply suspect. Around the world, though, there are probably at least another 30M people who could read and enjoy your book in standard French, or slightly tweaked French (such as Quebecois). Official French figures put the size of the French speaking world at over 900M if you include all variants and all people speaking French as a second language. I'm going with the lower figure.

That gives you a target population of 90M - call it 100M for ease of calculation, so one fifth the size of the English speaking population. So one fifth of 5000 download sales at $1.50 or nearest local currency; call it $1.45 to factor in currency exchanges and fluctuations: $1450

Your 75k word book will cost you anything from $5000 to $10000 to translate into French. Horrifying isn't it? But anything lower is a slave-wage for a translator - and in any case a literary translation is complex and difficult, and as much a creative as an interpretive art.

You would need to sell 4000 downloads to make a profit. Lets try something a little more expensive:

Your 150k tome currently downloads for $5.99, and to date you have sold on average 500 copies per month. You can expect to sell 100 copies (or less) a month in French. Cost of translation $10k to $15k. You'd take 17 months to break even.

The point is that you can compare your sales in one language to potential sales in another to find out if translation will be profitable. As far as I can see, it should be profitable to translate anything relatively short (less than 80k words) that sells fast.

I'm already hearing rumours and ideas circulating among translators to set up translation and promotion services for any indie book that is already doing well enough in English to be profitable for translation. The French and German economies are large and affluent, "Global Economic Crisis" notwithstanding, and the sooner you break into these markets independently, the more you will encourage small, targeted intermediaries, rather than trad pub trying to get a stranglehold on translated releases by buying up foreign language rights and thereby maintaining their monopoly - albeit only on translated work.

2011-10-05

Weird Words: The Cat that got the Canary

In her new thriller, Cruel Justice, Mel Comley introduced me to the expression the cat that got the canary. This extremely evocative expression puts me in mind of Sylvester who, after long years of torment, finally manages to swallow that damn bird. In the context where Mel uses it, someone is feeling very pleased with themselves. An expression exists for this, and it is: the cat that got the cream.

This is an expression that has existed for a very long time indeed, and is an expression of smugness or self-satisfaction, as it describes the expression of the first cat at the churn, who gets to drink the cream on the top of the milk before the other cats arrive and have to make do with the milk.

This isn't quite what Mel was going for, though I think it would have fit. The cat that got the canary is somehow … predatory.

This is an expression that has existed for a very long time indeed, and is an expression of smugness or self-satisfaction, as it describes the expression of the first cat at the churn, who gets to drink the cream on the top of the milk before the other cats arrive and have to make do with the milk.

This isn't quite what Mel was going for, though I think it would have fit. The cat that got the canary is somehow … predatory.

2011-10-04

POV Confidence

Point Of View (POV), sometimes called person, or viewpoint, is a much analyzed and much deconstructed narrative technique. I think this is a mistake.

It is a very simplistic view — indeed it is a lie to children — that the experience of reading a story is one of associating, sympathizing, identifying, with a main character, and thereby imagining yourself in his place. We don't experience real life in such an insular, individualistic, egocentric way. We experience real life (much of the time) as a group; we see events and experiences through many pairs of eyes. When you witness some event, you cannot help but see the effect it has on others who witness it, though the expression, posture, movement. When you are caught up in some event, you experience it not only through your own thoughts and feelings, but those expressed on the faces of your companions, and the faces of witnesses and bystanders. Even when you are wholly alone (without any human company), your environment is as much affected by you as you by it, and as you witness your effect on your environment, so you experience your own actions from a separate (albeit inanimate) point of view.

But it is easy to get caught up in the lie of a single point of view. Not only does it simplify and de-mystify the work of the author, but it gives him the illusion of control. And that control is where it all goes wrong.

Broadly speaking, I classify POV as follows:

1. First person or non-first person.

This is an easy one most of the time. If the narrator says "I did this, I did that," then this is a first person narration. If the narrator says anything else, then it isn't. The issue is complicated by the fact that first person narration isn't always first person POV. Eh?

When the narrative conceit is of an agonist in some past event who decides to commit his account of the event to paper (as is the case in the Sherlock Holmes mysteries), the narrator will use "I" when talking about himself, but might not always restrict himself to his own point of view. He can do this because he is narrating after the fact, and is in possession of additional facts and testimonies that he did not possess at the time. Here is a (made up) example:

While I conducted a thorough examination of the cellar, Holmes, wearing his customary expression of patient perplexity, returned to the library where he began a lengthy perusal of the late Duke's papers. Little did he know that he was being watched.

In the above case, the author is not slavishly restricting himself to what the (imaginary) narrator knew at the time, but uses what Watson must have found out later. I call this "what I didn't know" narration. It allows a first person narrator to go beyond his own point of view, and as such deliver a more rounded story, by which I mean one that includes witnesses other than himself.

2. Strong or Weak point of view.

Strong or Weak might just as well be expressed as structured or organic, disciplined or instinctive. "Weak" is not mean pejoratively. Strong POV is when the writer decides that the reader may know only what the current central character could know. As I have already suggested, this is a little artificial, but handled skillfully can lead to a real thrill-ride. Hitchcock uses this conceit in film (Vertigo, NxNW). Strong POV may be applied in either first or third person. (Or in extreme cases, second person. I fact when writing in second person, only strong POV is possible. And really, really odd. Try it sometime.)

Weak POV is harder to define. I can say that it leads to fewer problems for editor and reader, and is much closer to what I think of as natural narration, which is the way that you might tell an anecdote — for amusement or otherwise. Weak POV is a matter of telling the reader what the reader needs to know to experience the story as the writer intends. When different characters are acting in concurrently in mutually remote locations (or just mutually invisible locations), a gentle shift of POV allows the narrator to avoid lengthy recapping:

Sir Bedevere fought tirelessly; no matter the cost, he had to get through to the castle before it was too late. Robin was counting on him to save the Princess from a fate worse than … Bedevere wasn't thining about it, he was concentrating on the steady rise and fall of his sword.

Even as Bedevere fought his way to her, the Princess was not idle. Hearing the noise of battle, and sensing here fate was near, she had begun tearing the bedsheets into strips and braiding them together. She looked up at the bars on the window, then down at her hips. She would, she concluded, have to squash.

If I applied strong POV to Bedevere, then by the time the hapless knight will have fought his way to the Princess' bower, she will be long gone, and the narrator will either have to backtrack, or have Bedevere discover her means of escape, or worse still, have her recount her escape to him three chapters later when he finally catches up with her. In a good story, there is never time for explanation.

But strong POV leads to far worse excesses.

The twins, Alice and Bob, have, by the end of chapter four, become separated. The writer is having a blast alternating chapters from Alice' point of view and then from Bob's. In chapter 5, Alice sees Doctor Acula (the bad guy) for the first time. The narrator gives a suitably scary and ominous description of him, and he introduces himself and his evil schemes to Alice. Three chapters later, Bob espies Doctor Acula from a distance, and the writer finds himself in a rather silly quandary. How to describe the wicked Doctor such that the reader sense Bob's sense of foreboding without giving the reader the impression that Bob has recognized Doctor Acula, which of course he can't, since he hasn't met him yet? Of course, it can't be done without giving the reader the profoundly confusing impression that there are two very similar bad guys.

I encounter this over and over again. Even experience, well respected writers varnish themselves into this corner.

Here's another: Around chapter 10, an ambiguous secondary character, Craig, needs to be introduced. For his introduction he's going to do something dramatic: pull of a daring robbery. But to keep him mysterious, the writer can't use Craig's point of view. However, neither Alice nor Bob are present, but the writer has decided that every chapter must use a strong POV. So, the writer invents Dave the Security guard. Chapter 10 is written from the point of view of Dave, who is variously trying to prevent Craig from getting in, then trying to protect the Diamond, then trying to catch Craig before he escapes. At the end of chapter 10, Craig leaps away into the darkness and Dave falls out of a high window. End of Dave.

I know some writers will try to excuse this clumsy and blatant mechanism as pathos. I for one ain't taken in, and I reckon the same is true of most readers.

Finally, a word about head-hopping. Head-hopping is the much maligned practice of carelessly switching points of view within a single chapter, scene or even paragraph. At its worst it's really confusing, and it is really easy to mess up a narrative this way, so most editors will rightly discourage it, encouraging (I hope) using POV a little more weakly, or choosing one strong POV and sticking to it. However, head-hopping can be used to devastating effect.

In the first chapter of Mel Comley's new thriller, Cruel Justice, there is just one head-hop. It serves to accentuate the horror and brutality, and it is totally unavoidable. Read the first chapter here. Consciously or unconsciously, this is how to use POV.

POV isn't about what the character knows, it is about what the reader knows. EVERYTHING you write is about what the reader knows and what the reader feels and what the reader experiences. When you write, you aren't telling the reader what happened. You are using narrative to create an experience for the reader. The more you analyze and deconstruct your writing technique, the more you choose devices, styles, conceits because you like them, you know about them, you have seen others using them, the more you are writing for the benefit of the text, yourself, other writers and (heaven forfend!) critics.

Getting POV right is not about skill or technique, though. It is about confidence. And you get the confidence by knowing that you are telling the reader what he needs to know.

Do some live storytelling and you'll soon see.

It is a very simplistic view — indeed it is a lie to children — that the experience of reading a story is one of associating, sympathizing, identifying, with a main character, and thereby imagining yourself in his place. We don't experience real life in such an insular, individualistic, egocentric way. We experience real life (much of the time) as a group; we see events and experiences through many pairs of eyes. When you witness some event, you cannot help but see the effect it has on others who witness it, though the expression, posture, movement. When you are caught up in some event, you experience it not only through your own thoughts and feelings, but those expressed on the faces of your companions, and the faces of witnesses and bystanders. Even when you are wholly alone (without any human company), your environment is as much affected by you as you by it, and as you witness your effect on your environment, so you experience your own actions from a separate (albeit inanimate) point of view.

But it is easy to get caught up in the lie of a single point of view. Not only does it simplify and de-mystify the work of the author, but it gives him the illusion of control. And that control is where it all goes wrong.

Broadly speaking, I classify POV as follows:

1. First person or non-first person.

This is an easy one most of the time. If the narrator says "I did this, I did that," then this is a first person narration. If the narrator says anything else, then it isn't. The issue is complicated by the fact that first person narration isn't always first person POV. Eh?

When the narrative conceit is of an agonist in some past event who decides to commit his account of the event to paper (as is the case in the Sherlock Holmes mysteries), the narrator will use "I" when talking about himself, but might not always restrict himself to his own point of view. He can do this because he is narrating after the fact, and is in possession of additional facts and testimonies that he did not possess at the time. Here is a (made up) example:

While I conducted a thorough examination of the cellar, Holmes, wearing his customary expression of patient perplexity, returned to the library where he began a lengthy perusal of the late Duke's papers. Little did he know that he was being watched.

In the above case, the author is not slavishly restricting himself to what the (imaginary) narrator knew at the time, but uses what Watson must have found out later. I call this "what I didn't know" narration. It allows a first person narrator to go beyond his own point of view, and as such deliver a more rounded story, by which I mean one that includes witnesses other than himself.

2. Strong or Weak point of view.

Strong or Weak might just as well be expressed as structured or organic, disciplined or instinctive. "Weak" is not mean pejoratively. Strong POV is when the writer decides that the reader may know only what the current central character could know. As I have already suggested, this is a little artificial, but handled skillfully can lead to a real thrill-ride. Hitchcock uses this conceit in film (Vertigo, NxNW). Strong POV may be applied in either first or third person. (Or in extreme cases, second person. I fact when writing in second person, only strong POV is possible. And really, really odd. Try it sometime.)

Weak POV is harder to define. I can say that it leads to fewer problems for editor and reader, and is much closer to what I think of as natural narration, which is the way that you might tell an anecdote — for amusement or otherwise. Weak POV is a matter of telling the reader what the reader needs to know to experience the story as the writer intends. When different characters are acting in concurrently in mutually remote locations (or just mutually invisible locations), a gentle shift of POV allows the narrator to avoid lengthy recapping:

Sir Bedevere fought tirelessly; no matter the cost, he had to get through to the castle before it was too late. Robin was counting on him to save the Princess from a fate worse than … Bedevere wasn't thining about it, he was concentrating on the steady rise and fall of his sword.

Even as Bedevere fought his way to her, the Princess was not idle. Hearing the noise of battle, and sensing here fate was near, she had begun tearing the bedsheets into strips and braiding them together. She looked up at the bars on the window, then down at her hips. She would, she concluded, have to squash.

If I applied strong POV to Bedevere, then by the time the hapless knight will have fought his way to the Princess' bower, she will be long gone, and the narrator will either have to backtrack, or have Bedevere discover her means of escape, or worse still, have her recount her escape to him three chapters later when he finally catches up with her. In a good story, there is never time for explanation.

But strong POV leads to far worse excesses.

The twins, Alice and Bob, have, by the end of chapter four, become separated. The writer is having a blast alternating chapters from Alice' point of view and then from Bob's. In chapter 5, Alice sees Doctor Acula (the bad guy) for the first time. The narrator gives a suitably scary and ominous description of him, and he introduces himself and his evil schemes to Alice. Three chapters later, Bob espies Doctor Acula from a distance, and the writer finds himself in a rather silly quandary. How to describe the wicked Doctor such that the reader sense Bob's sense of foreboding without giving the reader the impression that Bob has recognized Doctor Acula, which of course he can't, since he hasn't met him yet? Of course, it can't be done without giving the reader the profoundly confusing impression that there are two very similar bad guys.

I encounter this over and over again. Even experience, well respected writers varnish themselves into this corner.

Here's another: Around chapter 10, an ambiguous secondary character, Craig, needs to be introduced. For his introduction he's going to do something dramatic: pull of a daring robbery. But to keep him mysterious, the writer can't use Craig's point of view. However, neither Alice nor Bob are present, but the writer has decided that every chapter must use a strong POV. So, the writer invents Dave the Security guard. Chapter 10 is written from the point of view of Dave, who is variously trying to prevent Craig from getting in, then trying to protect the Diamond, then trying to catch Craig before he escapes. At the end of chapter 10, Craig leaps away into the darkness and Dave falls out of a high window. End of Dave.

I know some writers will try to excuse this clumsy and blatant mechanism as pathos. I for one ain't taken in, and I reckon the same is true of most readers.

Finally, a word about head-hopping. Head-hopping is the much maligned practice of carelessly switching points of view within a single chapter, scene or even paragraph. At its worst it's really confusing, and it is really easy to mess up a narrative this way, so most editors will rightly discourage it, encouraging (I hope) using POV a little more weakly, or choosing one strong POV and sticking to it. However, head-hopping can be used to devastating effect.

In the first chapter of Mel Comley's new thriller, Cruel Justice, there is just one head-hop. It serves to accentuate the horror and brutality, and it is totally unavoidable. Read the first chapter here. Consciously or unconsciously, this is how to use POV.

POV isn't about what the character knows, it is about what the reader knows. EVERYTHING you write is about what the reader knows and what the reader feels and what the reader experiences. When you write, you aren't telling the reader what happened. You are using narrative to create an experience for the reader. The more you analyze and deconstruct your writing technique, the more you choose devices, styles, conceits because you like them, you know about them, you have seen others using them, the more you are writing for the benefit of the text, yourself, other writers and (heaven forfend!) critics.

Getting POV right is not about skill or technique, though. It is about confidence. And you get the confidence by knowing that you are telling the reader what he needs to know.

Do some live storytelling and you'll soon see.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)