Design is dead.

Time there was, in production fabrication and construction, the designer was the single most important contributor to development. Today, few people even understand what, back in their heyday in the nineteenth century, designers actually did, and when I point out exemplary pieces of period design, many folks will comment "Oh yes, there's lots of design on that".

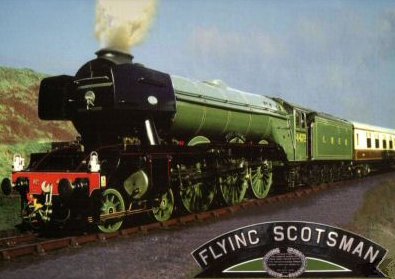

Time there was, in production fabrication and construction, the designer was the single most important contributor to development. Today, few people even understand what, back in their heyday in the nineteenth century, designers actually did, and when I point out exemplary pieces of period design, many folks will comment "Oh yes, there's lots of design on that".Somehow, design has come to mean "adding the pretty, nonfunctional details". Movements like Bauhaus are partly to blame. Bauhaus elevated design to an art form, but what made Bauhaus so aesthetically and ergonomically pleasing was its concentration on the principles that drove C18 and C19 engineering - the key being design. In the C19, design was the careful balance of functional requirements at all stages of the life-cycle of a product. The designer would, when deciding what his product would look like, take account of materials and their cost and availability, the cost, time and skill required for fabrication, the required durability, the costs of future maintenance, the necessity of future-proofing or backwards-compatibility (a couple of ideas that, under a variety of names, have been know since at least ancient Rome). The skill of some designers as the end of the nineteenth century approached was so great that they could afford to build-in beauty as a concomitant feature. In many areas of engineering, this idea continued through to the 1950s, and such visually divergent designs as Scotsman and Mallard…

… which solve similar practical problems but with strikingly different visual consequences. Both are beautiful, because their beauty goes so much further than external prettiness.

The high profile and high public approval of these kinds of design, combined with Bauhaus (and its imitators) elevation of aesthetics – or perhaps the elevation of Bauhaus by the popular press – resulted in a separation between the visual appearance of a product and its engineered function. Creative people with little or no knowledge of manufacture were brought in to "design" products to make them pleasing to the eye, popular, fashionable. These "designs" were then passed on to fabricators whose job was to find a way to manufacture something that looked like the designs.

This is how things are today. The real skill of fabrication is working out how to make something. Wherever this is understood, there are no designers at all; engineers invent, plan and build. The results seldom meet needs even when they meet requirements. (You know who you are.) Wherever there are designers, the engineers are woefully undervalued. Beauty has been divorced from function – indeed one often hears the two being described as in conflict: "a triumph of form over function" … "plain practicality".

To the engineers of the nineteenth century, as much as to the public who used their products, any design that solved a problem efficiently was inherently beautiful, and the satisfaction that they derived from the inherent beauty of a good solution, gave them the confidence to draw the bold flowing curves of the Mallard, and put Greek and Roman column capitals on gasometers.

In creative writing, design is seen by many as a sort of sell-out, betrayal or even circumvention of the artistic process. I have encountered this attitude as much in commercial writing as in novel writing. Setting aside marketing copy, novel writing is not, as many authors think, storytelling.

It has been accurately stated that the written word is the worst thing ever to happen to storytelling. Storytelling truly is an organic, creative, social process. When you tell a story to an audience, the audience responds to you and you to them. The story changes as it enters the imaginative space between you and your audience, and is different at each telling. Those of your audience whose imagination is captivated, will pass on your story to others, and it will change for them just as it changed for you.

When you write it down, it is the same every time you read it.

This gives you a problem to solve. How to tell the story that you want to tell, how to reach your audience when you don't have their reactions and you don't even know who they are? When you have a problem to solve, there is value in having a design. How far you take it is up to you – and is probably a function of your knowledge and experience. I suspect that many authors write as if they were telling a story with themselves as audience – which would explain the common observation by the author that the story took unexpected twists and turns, and that characters appeared, developed and evolved in unanticipated ways.

This stage is the discovery of the story. In storytelling, you discover the story either by being told it, or by telling it to yourself. Once you know your story, the practical problem to which you must return is "how to tell it using the written word". Most authors apply an iterative design process. Drafting and redrafting. Many authors involve third parties like beta-readers, proofreaders and editors (each of these has a different purpose and they should be selected to match your design process. Not every author can benefit from a literary editor). I guess the big advantage of novel writing is the possibility of design-after-the-fact. (I nearly said that in Latin, but I suspect that italics and hyphens is going to reach a larger audience.) Once you know the story, and have tried it out a few times, you can have several gos at writing it. My client, new writer Damon Courtney, has just sent me a redraft where he has made very substantial changes to the book, in structure, character dynamics, setting - even the outcome of major events (a party that had been planned then cancelled in the previous draft actually takes place in the new draft). The new draft is nonetheless the same story. But Damon has redesigned the way it is told to better match the medium: the written word.

The differences between "The Resurrection of Deacon Shader" and the rewriting "Shader: Cadman's Gambit" and "Shader: Best Laid Plans" are more than substantial. It's more a case of a few passages and characters from Resurrection being re-used in a new book. New book, same story.

If you are already a great author, chances are you probably ought to carry on doing whatever it is you do. If you want to become a great author, designing a book is complex and difficult. But worth it.

No comments:

Post a Comment